My memories of adolescence often visit me as a colorful bouquet of half-remembered scenes—of discovering new books, of discovering new music (back in those days, you were considered a connoisseur who possessed the most esoteric of tastes if your iPod was filled with the albums of Linkin’ Park, Nirvana, and Poets of the Fall), and watching reruns of the Harry Potter films and F.R.I.E.N.D.S in the neighbor’s cable-connected television.

Between my undying obsession of reading about the adventures of a certain green-eyed son of Poseidon and the enigmatic genius of a certain teen-aged criminal mastermind, my afternoons in the weekends were often spend begging the lords of the dial-up connection to bless me with speedy internet so that I could listen to the music that was liked by the girls higher up in the social hierarchy of my convent school. You see, it always seemed that these beautiful ladies lived in a separate realm altogether. And I, self-pitying, insecure and corpulent, was always chasing their greatness. When they spent their afternoons pining over Daniel Radcliffe and Robert Pattinson, I was still trying to hide my not-so-secret crush over Alan Rickman. When they listened to Taylor Swift, Jennifer Lopez and Shakira in their iPods, while mooning over boys who listened to Scorpions, Queen and Pink Floyd, I was still struggling with my addiction to cheesy Bollywood songs. And now, I cannot help but laugh at the shared cluelessness of it all. Adolescence, although painful, has hoarded my favorite stories.

But why this sudden soliloquy? You see, this afternoon, I cannot help but remember this old pang of obsessing about the wrong man while growing up. The good girls of the class mooned over Darcy, as I pledged my dreary soul to a certain wife-hiding Edward Rochester. The good girls dreamed about Disney’s Aladdin, and I was still stuck crying buckets over the Beast turning into the prince. The forbidden fruit, the dangerous idea, had always captured my heart. And it seems that literature and entertainment media is not far from such captivating portrayals either.

In the April of 2011, along with the rest of the world, there began my half-a-decade worth obsession over Game of Thrones. And let’s face it, the show, with its thousand and one faults, did change the viewership and perception of medieval fantasy shows in television. Suddenly, you were not supposed to cackle over overly fluffed-up gowns, like the ones in Black Adder. Suddenly, the queen was worse than the Wicked Witch, and let’s face it, we would all give a limb to stab Joffrey, our prince, multiple times. Game of Thrones was a game-changer, but it also set to establish a recurring plot motif that, though already preexistent, was not set upon stone just yet.

Let’s go way back to the first episode of Game of Thrones. A certain sequence where the young Daenerys is raped on her wedding night by her husband Drogo as she watches the sun set over the Narrow Sea. And yet, she makes the most of her situation, learns how to pleasure her husband and herself, and even bonds romantically with the barbaric Dothraki lord. And to this day, her relationship with Drogo is considered the most memorable, if not a continuing fan favorite, in the fan base. So, of course, you can comprehend the magnitude of the shock I felt when I finally got about reading A Game of Thrones in 2013, where I discovered that Drogo, in spite of being a violent Dothraki, did not actually rape his bride. Instead, he asked for her permission, which, although hesitant, Daenerys gave. Does that mean consensual sex sells less than the portrayals of rape? Is the easiest trope of establishing the brutality of a male character often relegated to sexual abuse? Is abuse, emotional or sexual, becoming the recurring plot narrative of establishing character depths of antiheros in modern television, films and books?

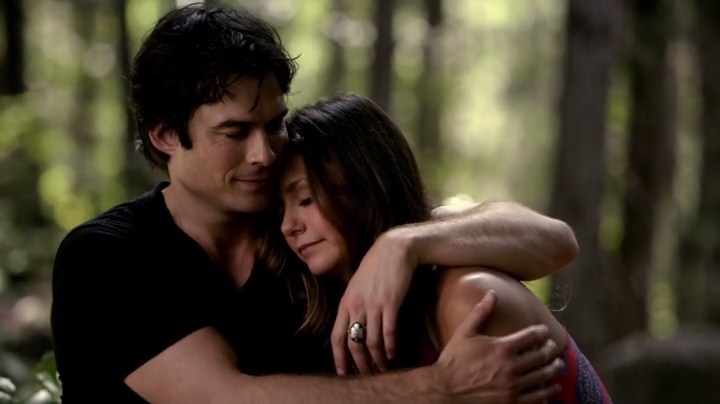

Leaving the trail of bloody innards and swords, let’s come to mainstream entertainment. From 2009 to 2017, The Vampire Diaries had quite the swansong of a television run. Although the ratings dwindled over the seasons, it still succeeded in being a mainstream phenomenon. And it did introduce Ed Sheeran to a much bigger fan base. However, observations apart, let’s talk about Damon Salvatore, the unpredictable and dangerous elder brother of the brooding Stefan, and his never-ending obsession/love toward the protagonist, Elena Gilbert. Damon was the quintessential bad boy. The showrunners used the age-old narrative to always keep the viewing audience on their toes as to whether the older Salvatore brother would ever be in the receiving end of redemption, in spite of centuries of ruthlessness. As inevitability would have it, he did become the staple “good guy” (or as far as Damon Salvatore can hope to be) and also got the girl. But here’s the thing. Let’s go back to the character Julie Plec started with. Here was this bloodthirsty vampire hell bent on ruining every nuance of peace his younger brother had and leaving a bloody trail behind while doing so. Damon seduces Elena’s closest friend/rival, Caroline Forbes, and using what the TVD mythos called “compulsion”, went on to use her as a blood bag for sustenance, while also emotionally and sexually abusing her in more than one occasion. So here’s the question. Is the new-age Byronic hero subverting into a sexual predator? It seemed that the showrunners completely forgot about this subplot as they went on to turn Caroline Forbes into the undead, while simultaneously humanizing Damon at the same time. On that note, humanizing the antagonists is a favorite trope of TVD. From Elijah to Klaus to Rebekah, almost every antagonist has been on the receiving end of such treatment. However, with Damon the cord snapped from logic a little too further away for the liking. Even while pursuing a relationship with Elena in the later seasons, Damon was prone to violent fits, unpredictable blood rages and a persistent underlying turmoil in the dynamics of the relationship, to the extent that the female protagonist was equally influenced and on the receiving end of the chaos. The result of this haywire plot was that the characters that they initially started out with lost the sketches that made their backbones and instead the audience was presented with a premature and mediocre hash of an unfeasible and illogical ending. Damon’s character deconstruction thus made a fundamental cornerstone in the holistic distortion of the show itself. On that note, the Twilight series (books/films) deserves a special mention. Dealing with the same mythos of vampires, it took a more vanilla take on the bloodthirsty mythical beings and unfortunately established some rather toxic tropes that were used repeatedly throughout the plot. From the stalker-like tendencies of Edward Cullen to the nigh invisible growth chart of the female protagonist’s character, Twilight was a rollercoaster ride into all things misplaced in both literary and film media. Dealing once again with the idea of being attracted toward the predator, or the “bad boy”, Twilight overused this motif to the point of making it a misunderstood representation of the modern girl’s idea of the perfect man. And with the millions of copies that the series sold, alongside the whopping 3.3 billion dollars worth of money it churned at the box-office, the Twilight phenomenon raged during its time. From posters of Edward Cullen to tee shirts that read Team Jacob and Team Edward, and yes, to even a spoof film, Twilight’s influence was beyond imagination. After all, mockery is the highest form of flattery at times, isn’t it?

But then again, promoting abusive relationships as a form of plot narrative is a tale as old as time. In the 90s, the modern woman was hooked to a certain HBO TV series, Sex and the City. And the men would often see the show, in secret of course, to moon over the ladies and to comprehend the female mind. Sex and the City was a pioneer of its kind. Here was an unabashed sex comedy that supposedly offered a keen view into the female brain, about their ideas about relationships, life and yes, sex. Candace Bushnell became an instant bestseller and the show cemented Sarah Jessica Parker’s career graph as the newest starlet of Tinseltown. Here was this bold and beautiful sex columnist who spoke her mind, struggled to pay rent and partied in New York City like it was the last night of her life. Here was this 30-something lady who cared little about time drying up her eggs and lived carelessly, in the midst of books and shoes, and in the warm company of her three best friends. And yet, like every other show with their misinformed ideologies of the so-called real people they often present their characters to be, Sex and the City drooped into being the same predictable romantic comedy at heart, while using a toxic relationship as its front-runner. Mr. Big, Carrie’s lifelong love, was a man who was afraid of commitments, to the point that their relationship was more often down the hills than soaring along the mountains. His constant fear of commitment, his laconic attitude, his pestering indecision, and most importantly, his inability to either walk away or give Carrie the validation of a partner that she needed were constantly misconstrued as characteristics that showed him to be the ever-untouchable idea of the bad boy. And his presence gradually wrecked the character growth of Carrie to the point that she became just another lovesick clueless woman who confused her roles, be it as Mr. Big’s girlfriend or his mistress. The emotional abuse wrought upon her altered the very strengths that Carrie’s character sketch initially banked upon: her brashness, her live-in-the-moment attitude. It even influenced her actions and disastrous impulses that led to the ruination of her other relationships, be it romantic or platonic. And thus began the six-season worth of the same old will-they-won’t-they plot motif. The disparity of her growth led to the unhealthy obsession that has been associated with Carrie’s character as well, and it is because of this, and several such factors, that has now relegated Carrie Bradshaw to be heralded as the quintessential example of a 90s train-wreck.

And talking about shoes and pretty dresses, how can we ever forget the 2007 to 2012 phenomenon, Gossip Girl? Gossip Girl was a step above Sex and the City, purely because of the reason that the show was self-aware of its thousand hypocrisies. Every character was more or less the caricatures of the ongoing lives of what we concoct the rich elite to have. In a way, while watching Gossip Girl, every one of us started off as the respective Dan Humphreys, writer or not, on the other end of luxury. We all had that one untouchable complicated and damaged dream girl, we all swooned over Blair’s luxuries in the showrooms of Gucci and Chanel, and we all envied Chuck and his endless series of debaucheries in his black limousine. Hell, we almost pitied Nate Archibald for being the clueless rich boy, lost in his haze of choosing morality or loyalty. In a way, we were all the watchers on the other side of the Brooklyn Bridge, and Gossip Girl never needed to take that glistened starlight away from its characters. And although it took precarious actions to humanize each of its characters, it never bothered to make them such so that its audience would find any form of relatability to them either; which was why the toxic undertones of the show were much more stilted than its contemporaries. You see, Gossip Girl was more insidious in its portrayals. In spite of its immense fan support, Chuck and Blair’s relationship was a rollercoaster of mistakes. Two extremely headstrong, proud, volatile and rigid characters, Chuck and Blair challenged each other in what can only be explained as something of a toxic competition. The whole chemistry of the two characters was based on the notion “can’t-live-with-each-other, can’t-live-without-each-other”. Over the course of the series, both characters become more and more embroiled in the sole purpose of sabotaging each others’ relationships with partners who weren’t themselves to the point that their character growths dwindled to their lowest. Blair from Season 1 still remained so in Season 6, at least on the surface, and her loyalties, though added to her magnanimity, it never truly humanized her to the extent where the audience could empathize with her character. On the other hand, the stereotypical bad boy persona that Chuck exuded only led to the predictable deconstruction of portraying him as the damaged rich boy with daddy issues in the later seasons, further deteriorating any opportunity of growth. And the fragility of their respective egos only mirrors the amount of emotional abuse either of them inflicted upon each other, be it through Chuck’s endless philandering or Blair’s unending vindictiveness. Promoting these two characters as their primary couple was thus a horrible decision from the showrunners, especially when the show itself had started with devolving each of its characters. Another example of insidious emotional abuse was Serena and Dan’s relationship. Although it could easily be predicted by any Gossip Girl loyalist that Serena and Dan would end up with each other, the whole show ran on the possibility and impossibility as to how these lovers would finally be together. And although the simplicity of their connection, the fact that each character completed what the other lacked, was the crux of their relationship, the showrunners made the fool’s choice to reveal Dan, the one observer of the lives of the elites, the only character the audience remotely related to, as the gossip girl. And that put the purity of his feelings toward Serena in question, as for time and again, the gossip girl has gone on to sabotage her privacy. The fact that the showrunners made Dan as the manipulator, and the insider, of the group, was possibly a poor imitation of what could have been the construction of a grey character. Unfortunately, nuances of such plot motifs can only be acknowledged as well-written when there has been a prior development in that trajectory in the past. Moreover, the recurring, if not gradual, growth of Serena and Dan’s personalities over the seasons only went on to show how incompatible they were for each other. From youthful teenagers to cynical adults with their own set of demons, Serena and Dan thrived better as individuals who led separate, if not disparate, lives. Thus, putting them in the same box they started from in Season 1 after going the distance was probably the worst written subplot in Gossip Girl.

Portrayals of abusive relationships, falling in love with the bad boy, the dangerous one, have always been a much celebrated plot motif in both literature and entertainment media. We have all spent afternoons shamelessly pining with Catherine over a certain Heathcliff in the moors of Thrushcross Grange. We have all adored Darcy’s incapability of expression toward the opinionated Elizabeth as the nights dwindled toward dawn in between the pages of our wear-worn novels. But over the years, practicality has always won over. We could see the fallacies in such misplaced affections. In a way, this plot motif and our perceptions toward it has been a trajectory of our individual growth as well. However, many have taken the fall in such misplaced portrayals as well. I have witnessed men and women falling prey to the undying hope of attaining redemption in their failed love stories, questioning my lack of faith with such examples too. You see, falling in love with the wrong one is not necessarily an unforgivable affront toward humanity, not really. I myself have lived that same story over and over in my past. Yet, there was also courage to be found, the moment when each one of us understood that the story has finally ended and it was time to close the book, only to be opened to sift through its pages in those dreary nights of lonesomeness in years far, far away. So here’s to all the bad choices, the unfinished stories, and the broken beautiful ones; and here’s to hope, to courage, and to choosing oneself over every love story ever written.